Donate

Support us in the fight for a better food system.

As COP30 arrives in Brazil, deforestation and its drivers must take centre stage. But will the farmed salmon industry get the scrutiny is deserves?

If you’ve followed Foodrise’s work on aquaculture, you’ll know that the salmon industry extracts vast quantities of wild fish – much of it from the Global South – to feed the farmed salmon that end up on European dinnerplates.[1] But what’s less well known is the salmon industry’s similarly voracious appetite for soy.

Farmed salmon is devouring both the ocean and the rainforest, harming people and planet in its wake.

In Belém, the world’s spotlight will rightly be on Amazon deforestation, which is in part driven by soy production. Global soy production has sky-rocketed over the past 50 years and is now more than 13 times higher than it was in the early 1960s.

Brazil is at the heart of this boom. In 2023, it became the largest producer of soybeans, with exports which hit a record just last month (October 2025). Three decades ago, only four of Brazil’s nine Amazonian states planted soya beans; today, all nine do, making it Brazil’s fastest-growing commodity.

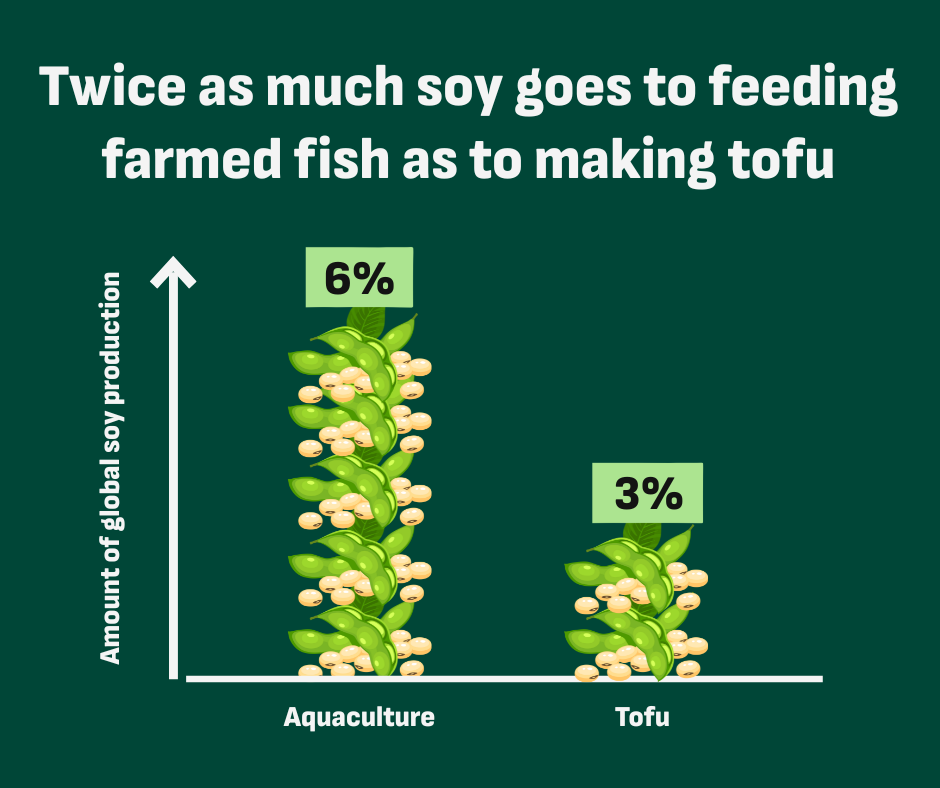

This huge growth is primarily down to the increasing demands of industrial livestock and aquaculture. Nearly 80% of global soy is turned into animal feed, with nearly 6% going to aquaculture alone. This is more than double the amount that goes towards making tofu (2.6%).

Without tackling global appetites for meat, animal products and farmed fish, demand for soy – and the environmental devastation it’s causing – will only continue to grow.

Advertising from the global salmon industry would have you believe that farmed salmon is the ‘climate-friendly’ option, but its outsized demand for soy, alongside its rapacious appetite for wild-caught fish, shows otherwise. The reality? Farmed salmon is a key player in driving the extraction of soy and it should not be overlooked.

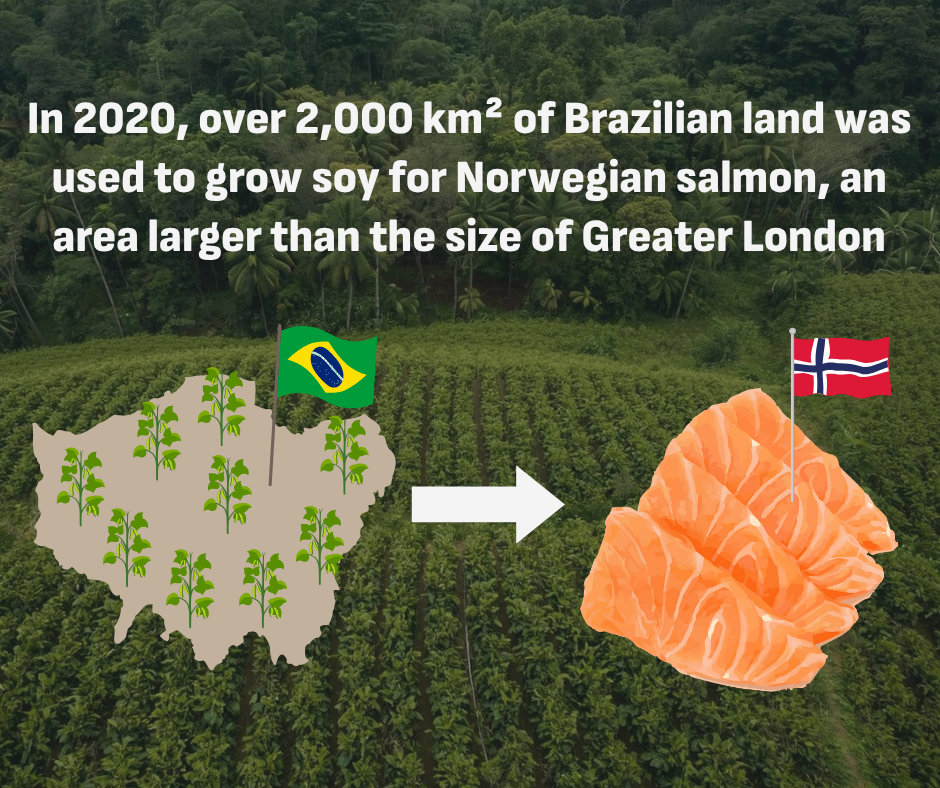

In 2020, Norway imported around 370,000 tonnes of Brazilian soy protein concentrate to feed farmed salmon. The land required to grow the soy in Brazil to feed Norwegian salmon in 2020 was 2,154 km2 – an area larger than the size of Greater London.

Foodrise’s research shows that major salmon producers – Mowi, SalMar, Lerøy, Bakkafrost and Grieg – all source soy from Brazil.

Farmed salmon’s demand for soybeans drives a cascade of environmental destruction:

And the damage doesn’t stop there. Soy production is also linked to serious social injustices, including slave labour, shocking working conditions and the displacement of small farmers and Indigenous peoples.

According to the Rainforest Foundation Norway report ‘Salmon on Soybeans’, the soy industry’s expansion is intensifying land conflicts between Indigenous groups and farmers. For example, in the Guarani-Kaiowá territory, soy plantations now occupy disputed lands claimed by Indigenous communities, leading to ongoing violence. Just last year, when Indigenous people attempted to reclaim their land, they were attacked by farmers, leaving 11 people injured.

Without cutting our global demand for meat, dairy, and farmed fish, soy-driven destruction will only grow.

At COP30, world leads must act to break this cycle of exploitation and stop the farmed salmon industry from devouring Brazil’s forests and eating up the Amazon in the name of profit.

Amelia Cookson is Aquaculture Campaigner at Foodrise

Learn more about the impacts of salmon farming here: Blue Empire, Fishy Finances

[1] Research published in 2024, suggests that it takes up to 6 kilograms of wild-caught fish to produce just 1 kilogram of farmed salmon (https://www.science.org/doi/epdf/10.1126/sciadv.adn9698).